|

| Cayo margarita, C. galbinus & C. refulgens Bieler, Collins, Golding & Rawlings, in Bieler, Collins, Golding, Granados-Cifuentes, Healy, Rawlings et Sierwald, 2023. DOI: 10.7717/peerj.15854 |

Abstract

Vermetid worm-snails are sessile and irregularly coiled marine mollusks common in warmer nearshore and coral reef environments that are subject to high predation pressures by fish. Often cryptic, some have evolved sturdy shells or long columellar muscles allowing quick withdrawal into better protected parts of the shell tube, and most have variously developed opercula that protect and seal the shell aperture trapdoor-like. Members of Thylacodes (previously: Serpulorbis) lack such opercular protection. Its species often show polychromatic head-foot coloration, and some have aposematic coloration likely directed at fish predators. A new polychromatic species, Thylacodes bermudensis n. sp., is described from Bermuda and compared morphologically and by DNA barcode markers to the likewise polychromatic western Atlantic species T. decussatus (Gmelin, 1791). Operculum loss, previously assumed to be an autapomorphy of Thylacodes, is shown to have occurred convergently in a second clade of the family, for which a new genus Cayo n. gen. and four new western Atlantic species are introduced: C. margarita n. sp. (type species; with type locality in the Florida Keys), C. galbinus n. sp., C. refulgens n. sp., and C. brunneimaculatus n. sp. (the last three with type locality in the Belizean reef) (all new taxa authored by Bieler, Collins, Golding & Rawlings). Cayo n. gen. differs from Thylacodes in morphology (e.g., a protoconch that is wider than tall), behavior (including deep shell entrenchment into the substratum), reproductive biology (fewer egg capsules and eggs per female; an obliquely attached egg capsule stalk), and in some species, a luminous, “neon-like”, head-foot coloration. Comparative investigation of the eusperm and parasperm ultrastructure also revealed differences, with a laterally flattened eusperm acrosome observed in two species of Cayo n. gen. and a spiral keel on the eusperm nucleus in one, the latter feature currently unique within the family. A molecular phylogenetic analysis based on mitochondrial and nuclear rRNA gene sequences (12SrRNA, trnV, 16SrRNA, 28SrRNA) strongly supports the independent evolution of the two non-operculate lineages of vermetids. Thylacodes forms a sister grouping to a clade comprising Petaloconchus, Eualetes, and Cupolaconcha, whereas Cayo n. gen is strongly allied with the small-operculate species Vermetus triquetrus and V. bieleri. COI barcode markers provide support for the species-level status of the new taxa. Aspects of predator avoidance/deterrence are discussed for these non-operculate vermetids, which appear to involve warning coloration, aggressive behavior when approached by fish, and deployment of mucous feeding nets that have been shown, for one vermetid in a prior study, to contain bioactive metabolites avoided by fish. As such, non-operculate vermetids show characteristics similar to nudibranch slugs for which the evolution of warning coloration and chemical defenses has been explored previously.

Thylacodes bermudensis Bieler, Collins, Golding & Rawlings n. sp.

Cayo n. gen.

Type species: Cayo margarita n. sp., as described below.

Other species originally included: Cayo galbinus n. sp., Cayo refulgens n. sp., and C. brunneimaculatus n. sp., as described below.

Etymology: Cayo (male noun), the Spanish term for a small low island in the Caribbean and surrounding regions, equivalent to “key” in Florida, “cay” in the Bahamas, and “caye” or “cay” in Belize. Here referring to the type localities of the four currently known species of this genus, Looe Key in the barrier reef of the Florida Keys and Carrie Bow Cay in the Belizean reef.

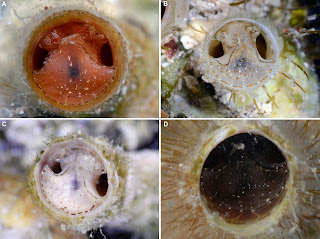

Diagnosis: Vermetids with small to medium-sized shells that are sculptured with densely spaced undulating growth marks and, in some species longitudinal cords on the adult whorls; white, often with brown markings on the outside and inside of shell. Attached to the substratum in the post-larval stage, often deeply entrenching into the substratum, living singly (not clustering), frequently forming very regularly expanding spirals in a Flemish flake pattern, resulting in near-circular attachment, occasionally with erect feeding tubes. The large pedal disk without an operculum, in some species with luminous yellow or yellowish green coloration lining edges or covering the entire head-foot. Females brooding stalked egg capsules (with the stalk attaching near but not at the terminal end) containing multiple eggs, which are attached to the interior shell through a shallow slit in the anterior mantle. Larval shell paucispiral and depressed. Fine granular sculpture in the columellar muscle region of the interior shell. Eusperm, where known, with laterally flattened acrosome.

Cayo margarita Bieler, Collins, Golding & Rawlings n. sp.

Etymology: margarita: Alluding to the vividly lemon-yellow coloration that this species shares with the citrus-juice-based cocktail drink (noun in apposition).

Cayo galbinus Bieler, Collins, Golding & Rawlings n. sp.

Etymology: galbinus, -a, -um: Latin for greenish-yellow, referring to the vivid head-foot coloration (adjective).

Cayo refulgens Bieler, Collins, Golding & Rawlings n. sp.

Etymology: refulgens: “shining back” or, figuratively, “standing out” (used as adjective), here referring to the luminous yellow lining surrounding the pedal disk and mouth region.

Cayo brunneimaculatus Bieler, Collins, Golding & Rawlings n. sp.

Etymology: brunneimaculatus, -a, -um: from Latin brunneus (brown) and maculatus (spotted, blotched) (used as an adjective). Referring to the brown pattern in both the soft body and teleoconch coloration in this species.

Conclusions:

There has been an independent loss of an operculum at least twice in the history of Vermetidae. The two clades, Thylacodes and Cayo n. gen, differ in many morphological and behavioral features (including larval shell and eusperm morphology, substrate-entrenching behavior, overall shell size, and expression of polychromatism) and belong to different branches of the vermetid tree. These results add to the accumulating evidence that convergent evolution is more common than has been widely appreciated (Blount, Lenski & Losos, 2018). In this case, the development of a robust phylogenetic hypothesis supported by morpho-anatomical, ultrastructural, behavioral, developmental, and molecular data enabled the recognition of convergence. The severe constraints of a sessile filter feeding lifestyle, with limited options for antipredatory responses, may also limit the range of adaptive solutions, leading to similar outcomes. Another example of adaptive constraints leading to similar outcomes in the mollusks is convergence in shell shape in swimming bivalves (Serb et al., 2017). Further comparative studies based on robust phylogenies will undoubtedly turn up additional examples, allowing us to arrive at an estimate of the frequency of, and optimal conditions for, convergent evolution.

Rüdiger Bieler, Timothy M. Collins, Rosemary Golding, Camila Granados-Cifuentes, John M. Healy, Timothy A. Rawlings and Petra Sierwald. 2023. Replacing Mechanical Protection with Colorful Faces–twice: Parallel Evolution of the Non-operculate Marine Worm-snail Genera Thylacodes (Guettard, 1770) and Cayo n. gen. (Gastropoda: Vermetidae). PeerJ. 11:e15854 DOI: 10.7717/peerj.15854