|

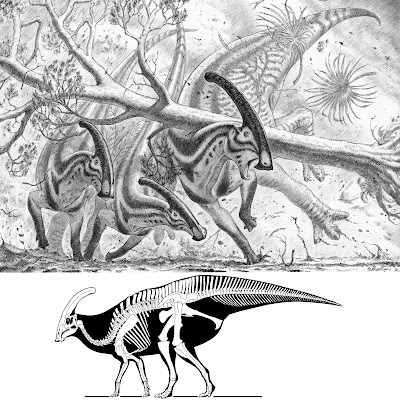

| Parasaurolophus walkeri Parks, 1922 Paleoart reconstruction of a plausible scenario explaining the fossilized injuries in the thorax of ROM 768. In a violent rain and windstorm, a large tree (Platanaceae) falls on an adult Parasaurolophus walkeri, while the group is escaping. The tree falls vertically on the back of the animal, hitting the rib cage and the neural spines of the anterior dorsal vertebrae. in Bertozzo, Manucci, Dempsey, et al., 2020. DOI: 10.1111/joa.13363 Artwork by Marzio Mereggia. |

Abstract

Paleopathology, or the study of ancient injuries and diseases, can enable the ecology and life history of extinct taxa to be deciphered. Large‐bodied ornithopods are the dinosaurs with the highest frequencies of paleopathology reported to‐date. Among these, the crested hadrosaurid Parasaurolophus walkeri is one of the most famous, largely due to its dramatic elongated and tubular nasal crest. The holotype of Parasaurolophus walkeri at the Royal Ontario Museum, Canada, displays several paleopathologies that have not been discussed in detail previously: a dental lesion in the left maxilla, perhaps related to periodontal disease; callus formation associated with fractures in three dorsal ribs; a discoidal overgrowth above dorsal neural spines six and seven; a cranially oriented spine in dorsal seven, that merges distally with spine six; a V‐shaped gap between dorsal spines seven and eight; and a ventral projection of the pubic process of the ilium which covers, and is fused with, the lateral side of the iliac process of the pubis. These lesions suggest that the animal suffered from one or more traumatic events, with the main one causing a suite of injuries to the anterior aspect of the thorax. The presence of several lesions in a single individual is a rare observation and, in comparison with a substantial database of hadrosaur paleopathological lesions, has the potential to reveal new information about the biology and behavior of these ornithopods. The precise etiology of the iliac abnormality is still unclear, although it is thought to have been an indirect consequence of the anterior trauma. The discoidal overgrowth above the two neural spines also seems to be secondary to the severe trauma inflicted on the ribs and dorsal spines, and probably represents post‐traumatic ossification of the base of the nuchal ligament. The existence of this structure has previously been considered in hadrosaurs and dinosaurs more generally through comparison of origin and insertion sites in modern diapsids (Rhea americana, Alligator mississippiensis, Iguana iguana), but its presence, structure, and origin‐attachment sites are still debated. The V‐shaped gap is hypothesized as representing the point between the stresses of the nuchal ligament, pulling the anterior neural spines forward, and the ossified tendons pulling the posterior neural spines backward. Different reconstructions of the morphology of the structure based on the pathological conditions affecting the neural spines of ROM 768 are proposed. Finally, we review the history of reconstructions for Parasaurolophus walkeri showing how erroneous misconceptions have been perpetuated over time or have led to the development of new hypotheses, including the wide neck model supported in the current research.

Keywords: Alberta, Cretaceous, nuchal ligament, Ornithopoda, trauma

|

| Paleoart reconstruction of a plausible scenario explaining the fossilized injuries in the thorax of ROM 768. In a violent rain and windstorm, a large tree (Platanaceae) falls on an adult Parasaurolophus walkeri, while the group is escaping. The tree falls vertically on the back of the animal, hitting the rib cage and the neural spines of the anterior dorsal vertebrae. Artwork by Marzio Mereggia. |

Filippo Bertozzo, Fabio Manucci, Matthew Dempsey, Darren H. Tanke, David C. Evans, Alastair Ruffell and Eileen Murphy. 2020. Description and Etiology of Paleopathological Lesions in the Type Specimen of Parasaurolophus walkeri (Dinosauria: Hadrosauridae), with proposed Reconstructions of the Nuchal Ligament. Journal of Anatomy. DOI: 10.1111/joa.13363